Basic organisational and technical approaches to the creation of successful mill production

General Director of LLC ‘OLIS’, Candidate of Technical Sciences A.P. Vereshchinsky.

Some agro-industrial enterprises and holdings, having succeeded in grain production, strive to create or expand its processing. Often in their field of vision there is a mill production for production of wheat variety flour. Our observations show that the majority of managers who master this new type of business are prone to errors in the choice of effective means of its implementation. Flour-milling production is characterised by deep specificity, which goes far beyond the stories of sales managers of this or that equipment manufacturer. In this article we will try to clarify at least the basic organisational and technical approaches to the creation of successful mill production without special introduction into technological aspects.

In Soviet times, the development of flour milling, as one of the main components of the country’s food security, was given great importance. At the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union, our flour-milling industry, like no other branch of the food industry, had world-class scientific, technical and production potential. This was the result of the large-scale re-equipment of the industry that began in the 70s. The re-equipment was based on the technologies and equipment of the Swiss company ‘Büller’. The domestic flour milling industry received not only the most advanced means of production from the world leader, but also the rights for their serial reproduction. Our science was supplemented with the world experience and reached the modern frontiers of implementation. At the same time, the basis of flour milling is mechanics, aerodynamics and biochemistry, which are not new and established sciences. The impetus for the development of technology and milling techniques, which began both at home and abroad in the post-war years, moved to the level of improvement by the end of the last century. Therefore, even nowadays it is not necessary to purchase imported equipment or to attract foreign specialists in order to create a modern, technically competitive mill production. We still have both. As practice shows, domestically built mills are at least three times cheaper than imported mills with the same performance indicators. Nevertheless, the boom of hastily equipped mini mills has been replaced by more tonnage production, but mostly imported. Among the technically backward, often artisanal equipment, there are productions of world leaders. However, the vast majority of them are also unable to ensure sustainable profitability of processing in our economic conditions. These production facilities were created for other milling, other wheat, designed for other operating conditions and other results. Thus, the huge payback period of the majority of newly created productions is the obligatory, but not the only payment of their owners for technical ignorance, as well as excessive trust to sellers of ‘advanced technologies’ and ‘know-how’.

Typically, most potential investors’ initial perception of a mill centres on the production building. Undoubtedly, it is an important part, but only a part of production. Any flour mill, even of the smallest capacity, in addition to the production building (the mill itself) necessarily includes a warehouse of raw materials, shop (warehouse) of finished products, a system of laboratory, operational control and management of the production process, a system of accounting and registration of operations with grain. In terms of their creation costs, the above components are comparable to the costs of the production building. However, without any of them successful production is impossible.

It is known that in order to ensure successful sales, the quality of manufactured products must meet regulatory requirements and be stable. In the case of flour, this condition can be fulfilled by processing grain with certain stable properties. However, incoming batches are always characterised by considerable variety. Obtaining a batch of grain of given characteristics (milling batch) is achieved by mixing two or three initial batches (components) in the required proportions. Changing the quantity or quality of the components in the grinding batch requires a change in processing modes, which is always associated with losses in quality and flour yield. In this regard, the grinding batch should be made for a long period of work, which requires a stock of initial batches of grain. Thus, the warehouse of raw materials should provide reception, separate placement, storage and supply to the production of initial batches of grain. Its capacity should allow uninterrupted provision of production with stable components of the grinding batch for at least 10 days of operation. Taking into account the need for separate storage of different batches, apart from the total capacity, an important aspect is the availability of separate containers by quantity. The storage can be either of floor type or silo type (elevator). However, when choosing the type of modern silos made of light steel structures, silos with cone bottoms should be favoured. Such silos are emptied completely when unloading, which does not require manual cleaning after storing each batch. The grain fed for processing must not exceed the specified contamination levels. Violation of such norms inevitably leads to a sharp decline in the quality of the flour produced. It is therefore desirable to equip the raw material warehouse with cleaning equipment. Advantage should be given to elevator separators, as mill separators are not productive enough for work in the mode of grain acceptance.

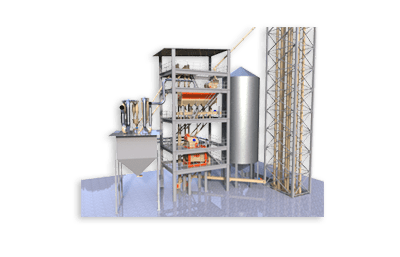

In the production building (the mill itself) the grain is prepared for milling and milled to produce the finished product – flour and bran. The main stages of preparation include preparation of the milling batch, grain cleaning and conditioning (moistening to a certain moisture content with subsequent holding in hoppers). In the milling department, the operations of multiple sequential-parallel milling and screening form the basis. The current trends in the development of milling plants aim at milling grain in a reduced structure. In this case, fewer units of equipment, less space, electricity, etc. are required, which significantly reduces the cost of establishment and operation. However, the exclusion of a number of technological operations and increased loads on equipment negatively affects the results of processing. Nevertheless, the effective conduct of such milling is proved by practice, although it requires special, especially careful preparation of grain. On the other hand, it is in the preparation of the grain that there are huge reserves for increasing the efficiency of processing at any milling structure. Therefore, when selecting or setting up a mill, maximum attention should be paid to the equipment of grain preparation facilities.

The technological process of milling is characterised by a hierarchical structure. However, the need for sequential and parallel processing results in a complex system of continuous movement of multiple streams, differing both in performance and quality of the products being moved. Movement of product streams along specified routes, as well as the possibility of operative change of their direction is provided by communication of mechanical, pneumatic and gravity transport. The most economical and technically expedient variant is vertically oriented communication, when the product is lifted upwards and processed, coming from machine to machine by gravity flow. The minimum number of ‘lifts’, as well as all transport devices, with maximum ‘manoeuvrability’ of routes, is provided by arrangement of the mill in several levels (floors). Mill layout ‘in height’ also creates favourable conditions for effective solution of a number of technical and technological tasks, which ultimately results in a significant increase in the quality and yield of flour. Practice shows that mills with a capacity of up to 100 tonnes per day should be built in four storeys, and above 100 tonnes per day in five or more storeys. Nevertheless, many mills are built ‘wide’. The implementation of such solutions is often caused by the customers’ desire to “fit” flour production into an adapted warehouse or hangar. In a number of cases, the developers sacrifice the storey in order to save bearing steel structures. The owners of such mills have to pay for the implementation of such solutions with their low efficiency.

There are always time gaps between flour production and its shipment to the consumer, which are used to prepare batches of finished products. This preparation can be done in several ways. At small capacity mills, flour grades are formed directly in the production building, and stored before shipment in finished product storage warehouses in bags, small containers and (or) in bulk form. With the increase in mill capacity, storing large volumes of flour in containers is problematic. Therefore, the flour produced by grades is stored in bulk form by sewing it into bags or packing it into small containers immediately before shipment. In such an organisation of cargo flows, the slaughterhouse, packing department and finished product warehouses are combined into a finished product department. Often there are situations when at the moment of grain processing in the production building it is not known what kind of flour, in what quantities, in what form and when it will be shipped. In such cases it is advisable to take several streams of flour out of the production building, store them separately in bulk and mix them to form the required grades as needed. Usually, the finished product department provides for flour enrichment with micro-additives, as well as bran granulation. Experience shows that in order to ensure uninterrupted operation of the mill in the conditions of modern economy, the storage capacity should be designed for at least 5-6 days of storage of all manufactured products.

The dependence of the results of milling on a huge number of heterogeneous factors does not allow to fully entrust the management of flour production processes even to the most modern and perfect machines. Flour milling technology is one of the most complex in the food and processing industry, and the qualification of a technologist, called a coarse maker in the old fashioned way, is more of a craft than a speciality. Thanks to the constant and qualified intervention of the coarse grinder in the grinding process, the technological modes at each stage of processing are ensured to be close to the optimum and, as a consequence, the best possible final results. For an objective assessment of the situation, the coarse grinder needs to have qualitative and quantitative indicators of production performance, which is ensured by the organisation and systematic performance of laboratory and operational control. Laboratory control is carried out by the production and technical laboratory (PTL). Operational control is carried out at workplaces by production personnel to ensure the established modes of operations and their efficiency.

For each shift of the production personnel it is obligatory to record the work done with the preparation of primary reporting documentation. The results of work are determined at the end of each shift and drawn up in accordance with the form adopted by the enterprise. However, they must contain complete and reliable information about the quantity and quality of grain transferred (accepted) in processing, production (transfer to the warehouse) of finished products, consumption of containers, waste disposal, etc. Safety of material values at all stages of movement in the production process is ensured only by their responsible transfer by quality (using laboratory control) and quantity (using weighing equipment). Determination of accurate performance indicators for a month or a decade is carried out by complete washing out of all the grain received for the reporting month with emptying all bins and stopping production, i.e. cleaning.

Trends in the development of domestic flour milling are determined by the limited realisation of flour on the scale of the only truly reliable partner – the domestic market. It is quite clear that in such a situation part of the flour milling industry will be represented by a dozen of national-scale productions supported, for example, by government orders or corporate attachment to large consumers. The second part is a multitude of regional-level productions with a capacity of 30 to 150 tonnes per day, significantly prevailing in terms of total processing volumes. From the point of view of economic feasibility, flour milling gravitates towards grain production sites, which are also locations with cheaper production space and labour. At the same time, such production facilities are targeted at not very distant urban consumers. These trends will be exacerbated as transport costs continue to rise. Creation of efficient and profitable flour-milling production facilities, taking into account the level of their technical complexity and capital intensity, is quite ‘affordable’ for both individual agro-industrial enterprises or holdings, and regional business in general. Therefore, the task of the overwhelming number of flour milling enterprises will be regional leadership, provided by further expansion of market access through the creation of production of pasta, bread, convenience foods, etc. The organisational and technical level of such enterprises should ensure strict minimisation of raw material and energy costs, manoeuvring within the framework of several ‘strong’ positions of the assortment, timely response to changes in demand and rapid filling of new product categories.

In conclusion, it should be noted that flour milling plants are complex engineering structures and they need to be created according to pre-designed projects. The level of technical tasks to be solved in the process of production creation is much higher than the level of competence of ‘operators’ even of the highest qualification. Such work can be carried out by groups of specialists with a deep knowledge of the necessary complex of knowledge, where flour production technologies occupy a central place.